- Home

- Richard Dunlop

Donovan

Donovan Read online

This painting of Maj. Gen. William J. Donovan greets the visitor to CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia. Donovan is considered the father of American centralized intelligence.

Copyright © 2014 by Richard Dunlop

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected].

Skyhorse® and Skyhorse Publishing® are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

eISBN: 978-1-62873-898-8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-62636-539-1

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

Foreword by Sir William Stephenson

Preface

Prologue

Part One: The Making of a Hero 1883–1918

1 The Boy from the Irish First Ward

2 Donovan the Young Lawyer

3 Relief Mission to Europe

4 Joining Up with the Fighting 69th

5 Rehearsal for War

6 A Wood Called Rouge Bouquet

7 Taking Hell with Bayonets

8 Wild Bill Leads the Charge

9 The Men We Left Behind

Part Two: The President’s “Secret Legs” 1919–1941

10 Siberian Adventure

11 Fact-Finding in Europe

12 Racket-Busting DA

13 With the Department of Justice

14 The Parade Passes By

15 Politics and Foreign Affairs

16 The Unfolding Crisis

17 Contagion of War

18 Confidential Mission to Britain

19 Back Door to the White House

20 Fifty-Trip Ticket on the Clippers

21 Playing for Time

22 Mediterranean Intrigue

23 The Intelligence Proposal

Part Three: Wartime Spymaster 1941–1945

24 Donovan’s Brain Trust

25 COI Sets Up Shop

26 Conducting Ungentlemanly Warfare

27 OSS Goes to War

28 Prelude to Torch

29 Professor Moriarty Joins the OSS

30 Partners with the Resistance

31 Tangled Webs

32 Behind Enemy Lines

33 “The Wine Is Red”

34 Preparing for the Peace

35 End of an Experiment

Part Four: The Cold War Years 1945–1959

36 Bringing the Nazis to Trial

37 Donovan’s Last Missions

Acknowledgments and Chapter Notes

Bibliography

Foreword

On the day in May 1940 that Winston Churchill became prime minister, he telephoned me at my London home to say that he was dining with Max Beaverbrook and suggested that I join them. The dinner party was a serious affair. Other guests included Boom Trenchard of RAF and Scotland Yard fame, General Weygand of France, and Bill Hughes, prime minister of Australia. With the port and cigars Winston rose from his seat and beckoned to me. We walked over to the dining room window, heavily draped because of the blackout. Winston said quietly to me, “Bill, you know what you must do at once. We have discussed it most fully, and there is a complete fusion of minds. So off you go. You will have the full support of every resource at my command, and God will guide your efforts as He will ours. This may be our last farewell, so au revoir and good luck.”

It may be that at this late date I am thought of mainly as having been a regional representative of British Intelligence in the United States. My original charter went beyond that and indeed, under the master code name of Intrepid, was soon expanded to include representation in America of all the British secret and covert organizations, nine of them, and also security and communications. In fact, the communications division of my organization was by far the largest of its type in operation, handling more than a million message groups a day. In addition, there was the responsibility of acting as a go-between for Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt. My work as British Security Coordinator became an all-encompassing secret service.

I must enlarge a bit upon what were my principal concerns when I arrived in New York in late May 1940. Obviously, the establishment of a secret organization to investigate enemy activities and to institute adequate wartime security measures in the Western Hemisphere in relation to British interests in a neutral territory were of importance, and American assistance in achieving this goal was essential. The procurement of certain supplies for Britain was high on my priority list, and it was the burning urgency of this requirement that made me instinctively concentrate on the single individual who could help me. I turned to Bill Donovan.

By virtue of his independence of thought and action, Donovan inevitably had his critics. But there were few among them who would deny that he reached a correct appraisal of the international situation in the summer of 1940. At that time the United States government was debating two alternative courses of action. One was to endeavor to keep Britain in the war by supplying her with material assistance of which she was desperately in need. The other was to give Britain up for lost and to concentrate exclusively on American rearmament to offset the German threat. That the former course was eventually pursued was due in large measure to Donovan’s tireless advocacy of it.

Immediately after the fall of France, not even President Roosevelt himself could feel assured that aid to Britain would not be wasted in the circumstances. I need only remind today’s readers that dispatches from the U.S. ambassadors in London and Paris were stressing that Britain’s cause was hopeless. The majority of the President’s cabinet was of the same opinion. American isolationism was given vigorous expression by such men as Charles Lindbergh and Sen. Burton K. Wheeler. Donovan on the other hand was convinced that, granted sufficient aid from the United States, Britain could and would survive. It was my task first to inform Donovan of Britain’s most urgent requirements so that he could make them known in appropriate quarters, and second to furnish him with concrete evidence in support of his contention that American material assistance would not be improvident charity but a sound investment.

Very shortly after I arrived in the United States, Donovan arranged for me to attend a meeting with Secretary of the Navy Knox, Secretary of War Stimson, and Secretary of State Hull, where the main subject of discussion was Britain’s lack of destroyers. The way was explored for finding a formula for the transfer of 50 overage American destroyers to the Royal Navy without a legal breach of U.S. neutrality and without affront to American public opinion. It was then that I suggested that Donovan pay a visit to Britain with the object of investigating conditions at first hand and assessing for himself the British war effort. Donovan conferred with Knox, and they jointly conferred with the President. Donovan left by Clipper July 14, on one of the most momentous missions ever undertaken by any agent in the history of western civilization.

I arranged that he should be afforded every opportunity to conduct his inquiries. I endeavored to marshal my friends in high places to bare their breasts. He was received in audience by the king. He had ample time with Churchill and members of his cabinet. He spoke with industrial lea

ders and with representatives of all classes in Britain. He learned what was true—that Churchill, defying the Nazis, was no mere bold facade but the very heart of Britain, which was still beating strongly.

Donovan flew back to America in early August, and shortly after his arrival I was able to inform London that his visit had been everything I had hoped for. Donovan and Knox pressed the destroyers-for-bases case with the President despite strong opposition from below and procrastination from above. At midnight of August 22, 1940, I was able to report to London that the destroyer deal was agreed upon, and that 44 of the 50 ships were already commissioned. It is certain that the destroyers-for-bases deal would not have eventuated when it did without Donovan’s intercession, and I was instructed to convey to him the warmest thanks of His Majesty’s Government.

My work with Donovan could be described as covert diplomacy. There were other supplies that he was largely instrumental in obtaining for Britain during the same period. Among them were 100 Flying Fortresses for RAF Coastal Command and a million American rifles and 30 million rounds of ammunition for the British Home Guard, who were then mock training with broomsticks. During the early winter of 1940 His Majesty’s Government was especially concerned to secure the assistance of the U.S. Navy in convoying British merchant shipping across the Atlantic. This was a measure of intervention that the U.S. government was understandably reluctant to take. Donovan pleaded the case for us at a meeting with Knox, Stimson, and Hull in December 1940. This conference led to Donovan’s second trip. There was more to it than that, since Churchill wanted an influential American to apply some subtle delaying tactics in Bulgaria and Yugoslavia, which might affect the timetable of Hitler’s expected attack on Russia.

Donovan’s achievements in Britain and in the Mediterranean and Middle East were highly significant. When he returned to Washington on March 18, 1941, he brought with him a very comprehensive situation report with which to enlighten the President. At breakfast with President Roosevelt, he was assured of active support for a step that, as far as we British were concerned, was as water to a parched man dying of thirst—direct transportation of war materials to the Middle East. Two weeks later the ships were loading. These are only some of the highlights of Donovan’s accomplishments during this critical time.

From the beginning I had discussed with Donovan the necessity for the United States to establish an agency for conducting secret activities throughout the world, an agency with which I could collaborate fully by virtue of its being patterned after my own organization. He early agreed in principle, and on his first two visits to England he spent some time with British Intelligence, Special Operations Executive, and other similar agencies, both at headquarters and field training stations. Upon his return from his second visit, he discussed with the President the need for expanding the scope of American secret activities.

The idea that Donovan himself should direct the new agency that we envisaged did not at first appeal to him, nor was it by any means a foregone conclusion that he would be offered the appointment. Yet I was convinced that he was the obvious man for the job. In the first place, he had the confidence of the President, the secretary of state, and of the civilian heads of the service departments. In the second place, he had been involved in intelligence work for most of his adult life and he had given considerable thought to the conduct of secret activities. Third, Donovan had all the requisite vision and drive to build swiftly an organization of sufficient size and competence to play an effective part in the war. Last, he had already shown his willingness to cooperate fully with the British Security Coordinator and the worth of his cooperation had been abundantly proved. On June 18, 1941, Donovan informed me that he had seen the President and had accepted the appointment of coordinator of all forms of intelligence. The directive was necessarily vague in its terminology, but in fact Donovan had been entrusted with responsibility not only for collecting intelligence but for coordinating this work with preparations to conduct special operations and subversive propaganda. That night I could sleep.

DONOVAN: AMERICA’S MASTER SPY chronicles Bill Donovan’s entire life of service to his nation. Richard Dunlop, a former OSS agent who knew Donovan well during World War II and afterward, has brought to his work the very investigative flair and determined scholarship which his mentor, Bill Donovan, fostered in his aides. I worked closely with Donovan throughout the war, and my confidence in him proved to be fully justified. He was one of the most significant men of our century. It can be said for certain that before the war ended, Donovan’s OSS was comparable quantitatively with the combined efforts of British Intelligence and Special Operations Executive, in itself a commendable accomplishment. When it is remembered how little time he had to build his organization and how many serious obstacles he faced at the outset, this is truly remarkable. Qualitatively too, much of OSS’s work was without doubt of first-class importance by any standard.

Sir William Stephenson

Bermuda

May 1, 1982

Preface

When Dutch sculptor Kees Verkade was chosen to create a bronze tribute to Maj. Gen. William J. Donovan, he sculpted a 14-foot-tall figure of a tightrope walker. OSS men and women who attended the presentation ceremony in front of Columbia University Law School on May 24, 1979, thought that this was an appropriate figure to represent a man whose life had been an astonishing balancing act between a public career of soldier, statesman, lawyer, and humanitarian, and the clandestine life of an intelligence master.

Speaking at the presentation ceremony, John J. McCloy, assistant secretary of war when Bill Donovan was director of the Office of Strategic Services during World War II, remarked, “To class yourself as a colleague of Bill Donovan borders on the presumptuous. It carries connotations that may well not be deserved.” What is true of John McCloy’s relations to Donovan is many times over true of my own relations to him; but at the same time I can claim his friendship, and I still carry within me the extraordinary example of his life.

I had served Bill Donovan in a number of ways both abroad and in this country when one day he invited me to visit him at his law offices in New York. He commented that although I showed a certain aptitude for intelligence work, my talents were more suited to a career in journalism, for, he said, “You have an irresistible tendency to tell everything you know.” I was discomfited even though I immediately realized he was entirely correct. He went on to tell me about his own writing. He was then finishing an article for the Atlantic, which he asked me to revise for him. Later he interested me in his enormous research project to lay the basis for a history of intelligence in the western world.

And then he began to give me documents and material that, without his ever saying so, clearly were intended to help me to write his own life’s history. At breakfast in his apartment on Sutton Place, in his law office, or whenever we met on other business in Washington, Chicago, or New York, he invariably told stories drawn from his colorful past or discussed events in which he had played a pivotal if often secret part. Sometimes I would take notes, until he once remarked, “You should be able to remember things without scribbling on a piece of paper.” I put away my pen and notepad.

When Donovan was asked by President Eisenhower to go to Thailand as American ambassador, he asked me to accompany him, because of my knowledge of Southeast Asia in general and of neighboring Burma in particular. It proved impossible for me to go, and I have always had the nagging feeling that I let the General down. No matter, he was just as much my friend when we next met, and he was just as candid in his remarks about his experiences in Southeast Asia.

Bill Donovan himself made it possible for me to write this book, but he would not have expected me to write from his viewpoint alone. My wife, Joan, and I interviewed upward of 200 people who knew the General, and we worked in more than 40 archives. I traveled to France, the United Kingdom, Germany, Greece, and Thailand following Bill Donovan’s track. I talked to members of the Greek underground, and the French Resistance

, who knew him well, and I met Thais who still hope that his concept of an American foreign policy toward underdeveloped nations might yet be implemented. Everyone with whom I spoke at home and abroad appreciated that in Donovan they had known a most uncommon man.

Prologue

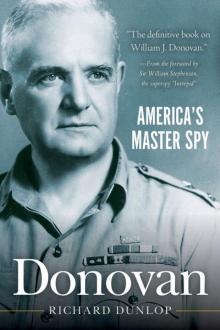

JUST WITHIN THE MAIN ENTRANCE of the Central Intelligence Agency headquarters at Langley, Virginia, a lifelike painting of a man in the uniform of a major general looks down on the comings and goings of CIA men and women. The four ribbons above the left breast pocket represent the highest awards the United States can confer, among them the Congressional Medal of Honor. His right hand is hooked in the pocket of his uniform, and his blue eyes seem to search the passing faces. There is no guile in his expression, only a disarming candor. Above all, the face gives the appearance of resolve, a manly purposefulness tempered by an innate gentleness of spirit. The painting is a portrait of William Joseph Donovan, lawyer, statesman, heroic soldier, diplomat, father of American intelligence, and America’s master spy—an enigma masked by charisma.

Thomas E. Stephens, the New York City painter admired for his more or less official portrait of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, painted Donovan’s portrait as well. It is judged an excellent likeness, even though Stephens had only two sittings before Donovan was stricken by a cerebral hemorrhage in the spring of 1957. The artist had to finish the work from a photograph that was a favorite of his subject, a picture Donovan countless times fondly inscribed to faithful members of his Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and resistance leaders who have since come in from the cold. Even now not all these former agents may feel it safe or politic to display the photo, given a world in which yesterday’s clandestine history and today’s behind-the-scenes events have a way of intertwining.

When Stephens finished the portrait, it was first hung within the entrance of CIA headquarters, then in the old South Building at 25th and E streets in Washington, D.C., on a hill overlooking a brewery and an indoor skating rink in the bottoms along the Potomac River. There Donovan once had his office. Although Donovan lay stricken at Walter Reed General Hospital, his brilliant mind a shambles, CIA Director Allen Dulles wanted him to be brought to headquarters to see the painting and the honor it did him. It was an act of sentiment since Dulles had learned his trade under the director of the OSS.

Donovan

Donovan